Raising teenagers has never been an easy task, but columnist Jenna Price believes today's parents have one distinct advantage she lacked in the 1990s: they can blame the government. As Australia grapples with debates around social media bans for young people, Price looks back on her own radical decision to strictly limit her children's television viewing, offering a wry perspective on the timeless struggle between parents, teens, and media.

The Great Television Crackdown of the 1990s

From 1998 to 2008, Price and her spouse navigated the turbulent teen years of their three children. Unlike today's parents, who can point to legislation, they had only themselves to blame for their household policy. Their approach was not an outright prohibition but a regime of strict limits on viewing hours, days, and crucially, content. The remote control was firmly in parental hands.

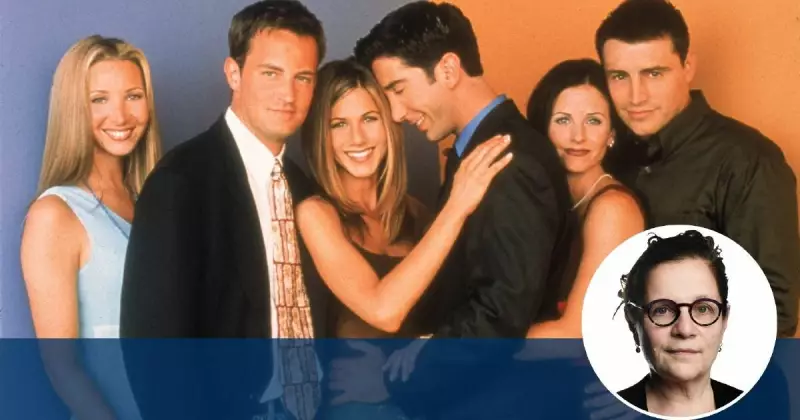

Their reasoning was multifaceted. By the early 2000s, medical journals were already highlighting the potential long-term harms of excessive television for youth, linking it to issues like obesity, raised cholesterol, and poor fitness. Yet for Price, the tipping point was cultural. She developed a deep concern about the influence of shows like Friends, which she viewed as promoting unrealistic beauty myths, stereotypes, and depictions of work and relationships. That popular sitcom was promptly banned.

Filling the Time and Facing Rebellion

The family's justification to their children was simple: "You have better things to do with your time." This philosophy launched a whirlwind of extracurricular activities. Schedules were packed with piano, cello, clarinet, choir, hockey, gymnastics, dance, swimming, drama, tennis, and Kumon classes. The goal was to be "broke but busy," leaving little room for the couch potato lifestyle they feared.

With both parents working more than full-time, constant surveillance was impossible in an era before smartphones. Predictably, the children found ways to rebel. They persuaded babysitters to bend the rules and visited friends whose households had more liberal television policies. However, Price believes the family's clear disapproval and ongoing discussions about media consumption kept the viewing somewhat in check.

Parallels to Today's Social Media Dilemma

Price draws direct parallels between her television limits and the current government-led social media bans. She notes that modern parents can deflect their teenagers' "pent up fury" towards politicians like Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, rather than shouldering the blame themselves.

She is under no illusion that her 1990s strategy would work today, but identifies one crucial element that remains valid: the necessity of continuous conversation. Her children constantly pushed her to justify the rules, forcing her to articulate clear reasons. This process of negotiation and explanation, she argues, led to a form of accommodation where the children understood the rules were made in their best interests.

Price also offers a realistic prediction: teenagers will always find a way. Just as her kids circumvented the TV ban, today's youth will likely get older siblings or friends to help them sign up for banned platforms. "Lying to their ageing parents. Manipulating friends. That's just the way it works," she writes.

Her final advice to parents navigating today's digital landscape is straightforward. Don't expect a busy schedule of activities to be a magic solution. Do expect your rules to be tested. Above all, "keep talking to them. Talking and talking. That appears to be the only thing which works." She signs off with a sympathetic, "Good luck. And may the force be with you."