In a reflective holiday column, The Canberra Times political analyst and ANU professor Mark Kenny tackles a pervasive modern ailment: the cynicism and doubt that paralyse progress. He begins with a Christmas Day conversation that questioned whether the iconic Live Aid concerts 40 years ago ultimately harmed Africa's economic prospects.

The Live Aid Legacy: A Lesson in Optimism

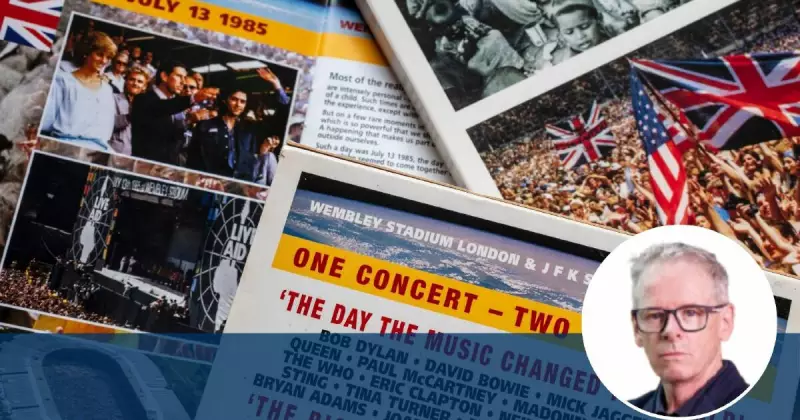

Kenny recalls the 1985 mega-concert, a 16-hour marathon broadcast from Wembley Stadium in London and JFK Stadium in Philadelphia to a global audience of up to two billion. Organised by musicians Bob Geldof and Midge Ure, it raised millions for famine relief in war-torn Ethiopia, representing a high point of collective humanitarian action.

Yet, he notes, some later analyses suggested that by highlighting the continent's poverty and crisis, Live Aid may have inadvertently discouraged long-term tourism and investment from wealthy nations. Kenny poses a powerful counter-question: even if this were true, does it invalidate the urgent mission to save lives during an acute emergency? His resounding answer is no.

"For me, though, the concern about such observations taking hold in the public mind is that they foster an already pervasive sense of doubt which in the end can become paralysing," Kenny writes.

Doubt as a Political Tool and Policy Paralysis

Kenny argues that doubt is the scourge of contemporary discourse, cheap to manufacture and weaponised against evidence-based action, citing climate change as a prime example. He observes that this culture of doubt is convenient for governments, providing a shield against radical or difficult policy reforms.

He points to Australia's own policy inertia, particularly in the housing sector. Politicians, he says, endlessly discuss increasing supply but "shelter in the doubt that anything more decisive could work" to avoid removing lucrative tax breaks like negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions. This protects the interests of the affluent while locking younger generations out of home ownership.

This paralysis, Kenny contends, leaves a litany of serious problems unresolved:

- Rising homelessness and wealth inequality

- Endemic mental health issues

- Aboriginal deaths in custody

- Violence against women

- Hospital overcrowding and aged care shortages

- Ongoing environmental destruction

Choosing Belief in Human Progress

Kenny suggests the festive season sharpens the contrast between society's haves and have-nots, making these contradictions feel more unconscionable. It is a time, he proposes, to reflect on accelerating materialism and the state of the world.

Returning to the example of Geldof and Ure, Kenny champions an optimism rooted in the possibility of human improvement over the prevailing cynicism. In the digital age, he warns, it is easy to tear down efforts and pick apart narratives of past progress, from the Moon landing to vaccine breakthroughs.

He references the storied 1914 Christmas Day truce during World War I. While the exact details of a soccer match in no-man's-land may be mythologised, the cessation of hostilities did occur. "Surely, humanity shining though in even the darkest moment is a story worth believing in - especially at Christmas?" he concludes.

Kenny's column is a call to resist the easy allure of doubt and to reaffirm a belief in collective action and the potential for positive change, both on the world stage and in addressing Australia's own entrenched challenges.